22.07.2019

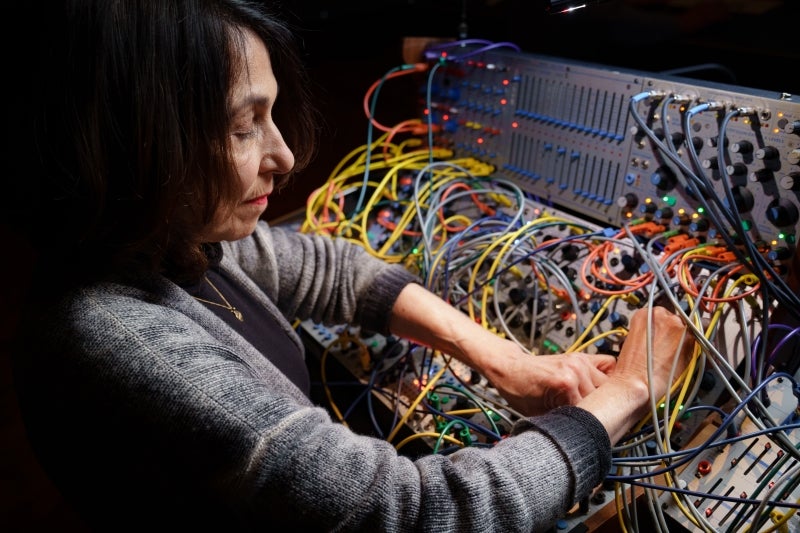

”Under the Electric Sea" an Interview with Suzanne Ciani

Credit: Dan Gizzie, Giovanni Dominice

Suzanne Ciani is undoubtedly a heroine of electronic music. Preparing for her upcoming ISM Hexadome shows in San Francisco and Montreal, we sat down with Suzanne Ciani to talk about the past, present and future. While studying composition at Berkeley in 1969, she met synthesizer pioneer Don Buchla and gave up her career as a pianist, only to solely dedicate her creativity to playing the "Buchla 200 Series Electric Music Box" – without much success. Apart from using no traditional keyboard as an interface, Buchla had designed his instrument around the idea to be performed on a quadrophonic sound system, a concept Ciani adopted and made mandatory for her performances.

The world was not yet ready. Instead of looking for gigs, Suzanne Ciani moved to New York in the mid-70s and turned her virtuosity playing the Buchla into a profitable job, becoming one of the most sought-after sound designers for tv commercials, image videos etc, producing iconic and now legendary sounds and jingles for companies like Coca-Cola, GE, Atari and AT&T. She went on to release a string of successful albums, which today are regarded as the foundation of New Age music and also feature her playing the piano, the instrument she had originally abandoned for the Buchla. Around 2015, her electronic productions were re-discovered, with both her commercial work and key Buchla concert being published for the first very first time. Since then, Ciani is back on the road, playing the Buchla and giving lectures about the instrument and the philosophy making it so unique. Today, her music is a perfect match for the ever evolving electronic music culture, its renaissance of analog modular instruments and passion for sophisticated multi-channel sound systems. Preparing for her upcoming Hexadome shows in San Francisco and Montreal, we sat down with Suzanne Ciani to talk about the past, present and future.

Interview: Thaddeus Herrmann

Photography: Giovanni Dominice

TH: Suzanne, thank you so much for taking the time to talk to us prior to your Hexadome show. Today, electronic music is everywhere, it is an integral part of pop culture worldwide. Sound systems do matter. However, quadrophonic or multi-channel set-ups are still quite rare. One might even think that those systems are a rather recent invention. Which is absolutely not true. How did you first learn about quadrophonic sound?

SC: Don Buchla introduced me to the idea. After I had finished graduate school and got my master in composition, I went to work for him, assembling his electronic music instruments. We didn’t call them synthesizers at the time, it didn’t seem appropriate, you know, the term had bad connotations. The music wasn’t synthetic at all. So, I took quadrophonic for granted, we worked like that from the beginning. This was in 1969. I’m pretty sure Don Buchla was the first one to come up with a spacial interface.

TH: It was part of the original design.

SC: Exactly, it was part of the 200 system and even more sophisticated than some of today’s techniques. Not only did we have voltage-controlled movement of the sound, which is very natural for electronic music. It should move. It is alive and we would integrate that motion with the rhythm of the music. We were also using a rather primitive spring reverb, which was voltage-controlled as well, so we could move the space close and far away. Voltage control plays an integral part in this idea, because it is fully integrated with the music. Today, we don’t use voltage control anymore, a lot of the spatial characteristics are applied the music after it has been produced.

This post-production spatialization is problematic in a sense, because if you try to move the sound it introduces a rhythm, which is not fully integrated with the natural rhythm of the music, it is in conflict. So it’s true – the quadrophonic concept is not really new. But when it was introduced in the early 70s, it failed. I think mainly because there was no content. Nobody knew how to use it. People were not interested in electronic music, let alone quadrophonic set-ups. The most common question back then was: "What are the other two channels for?" That attitude was especially frustrating for me, because I had the content. Being alive today to me is the fulfillment of a historic dream that I expected 40 years ago.

TH: Back then, you had your master in composition, had played the piano for a very long time and yet were willing to give all that up, a potential career, only to focus exclusively on the Buchla 200 system. A radical cut.

SC: Well, it was a radical time. Berkeley in the 60s was radical. It is true that I went there to study classical music. But one day, I was in a room playing Chopin and a rock came through the window. I looked outside and saw the demonstrating students, there was tear gas, craziness. Classical music didn’t feel appropriate anymore. Meeting Don Buchla changed me, transformed me even. He invented the first analog modular electronic instrument. Sure, Bob Moog was close, and people all over the world were working on instruments. All that doesn’t really matter anymore.

Don, though, followed his vision and not the marketplace. His idea was a performable music instrument, he was obsessed with the interface. When I came to work for him, I came under his spell and adopted his vision. One of his strongest concepts was to not confuse his design with a keyboard instrument. That would have ruined everything. And in fact, it did. Even though I was a pianist, I stopped the instrument I was accustomed to. We called the keyboard an "inappropriate interface". So I went out into the world playing the Buchla and soon realized that nobody understood what I was doing. At that time, people were familiar with the tape recorder and first thought the Buchla was just that. It was really frustrating. I figured out that I needed to be patient and communicative, explaining what it actually was. I’m still doing that.

TH: When you met Don and started playing the Buchla, were you aware of other electronic music around at the time? In the late 60s, electronic music was nothing new anymore. It had been around for quite some time in various incarnations. Musique concrète...

SC: I don’t call that electronic music.

TH: Why not? In the end, it is about oscillators, isn’t it?

SC: Well, everything is electronic when you play it through speakers. Anyway, of course I was aware of musique concrète. I was even doing my own experiments. I had worked with the father of computer music Max Mathews, studied with John Chowning, the inventor of FM synthesis, and had met some people from MIT and Bell Labs who were working in the field. But my deepest passion was the Buchla. I did take a class in Moog once, basically because I had to. During my last year of college, our department got a Moog system. At that time, I had already played with the Buchla and was completely adept. The professor in charge felt threatened by me and told me I was not allowed to touch the Moog before I got a certificate. So I attended the class, funnily enough given by Bernie Krause and Paul Beaver, and was still not allowed to use it afterwards. To me, this was one of many signs of the sexism ruling that era. There was a lot of it. Men were very uncomfortable, they looked at it as some kind of rivalry. At the time, I also took a conducting class, during which the professor told me: You know, women have no right on the podium. There were a lot of confrontations like that. The general feeling was that we, the women, were invading territory that men felt really was theirs. We just couldn’t believe it. If you think back the late 60s -- it was one of many peaks of female emancipation. We did bra burnings! I came of age in one of those peaks. But getting back to the question: These other ideas and concepts like musique concrète are electronic music in a sense and were brought into being by the invention of the tape recorder. All that is wonderful. In 1970, I even recorded my first album that way. I did "Voices Of Packaged Souls" in a radio studio, cutting and splicing tape.

Suzanne Ciani

Suzanne Ciani

TH: A classic set-up for the time.

SC: Very much so. Some sounds were done on a computer at Stanford, some others at Don’s studio and I brought all these pieces together and turned them into a composition. The appreciation of sonic materials as valid musical ingredients was certainly part of electronic music. You had a sound source from outside the acoustic world. But all that evolved very quickly. When keyboard instruments came around, everybody was suddenly interested in adapting acoustic instruments to electronic controllers. It got worse with MIDI. It’s fine, though. I, however, had already been introduced to a set of controls which was not dependent on a one-to-one correlation with a physical technique. I had voltage control and designed the voltages. In other words: I had a hundred hands. To me, that was always the most exciting part, when the machine took over. When keyboards came into electronic music, people suddenly thought, it was all about the sound everyone could identify with. "Do you hear that? It sounds like a flute. That’s a great sound, what sounds have you got?" I say: It is not about the sound itself, but how the sound can move. It’s alive. Anything sampled to me is dead on arrival. It’s not moving, has no energy.

It is not about the sound itself, but how the sound can move. It’s alive.

TH: That is a rather abstract concept when it comes to enable people to identify with the composition.

SC: Familiar timbres do not interest me. Just think about the constraints you end up having to deal with. When you study composition or orchestration, you learn about a family of acoustic instruments and then about their limits in ranges and playing techniques. It comes down to what you can actually write for a violin that is playable, how you can aggregate, balance and orchestrate all that, so that the sound is... beautiful. Or functional.

TH: Is beauty a problem in music?

SC: Not for me. But it also has to do with skills, how the orchestra cocks together. All that is based on limitations, though, whereas in electronic music, I can have a sound or an instrument that goes instantly from the bottom to the top, it is morphing all the time. When you play the Buchla, movement of sound is the key factor. Electronics can get static and many people explore exactly that state. This is what is called dance music! It’s one of many possible aesthetics, but not mine.

TH: An aesthetic which took a long time to develop. You’ve touched on the electronic music scene in the late 60s already -- back then, with "Switched-on Bach" Walter Carlos had created another one.

SC: As much as I did not consider musique concrète to be electronic music at the time, that album in particular to me was the beginning of the end of electronic music, it destroyed its future. Don’t get me wrong, Wendy – back the Walter – is a friend of mine. Back then, I got approached by record labels all the time, asking me to do a "Switched-on something". I always said no.

TH: So it was either adopting to what the record companies wanted or find a place in "serious" composition, blessed by academia.

SC: And I did not like the academic world at all, I told you earlier why. In fact, my generation of composers rebelled against it. It really was out of control -- music had gotten more and more complex, just to show off the skills of the composer, how they came up with something even more difficult. In electronic music, however, there was no difficult. There were no rules. If you wanted, you could do it all. Complexity was not an issue anymore, it was all programmable. Traditional composers did not see that and went further and further into complexity until a revolution happened, with people like Steve Reich, Philip Glass or John Adams just doing white-note music. We’re still in this phase. Academia just wants to look good and clever.

I can have a sound or an instrument that goes instantly from the bottom to the top, it is morphing all the time.

TH: You did commercial work instead. Which is logical in a sense, but might also be interpreted as being desperate.

SC: I wanted to record an album and basically had to finance it myself, since not a single record company was interested in what I did. Working with technology was incredibly expensive back then. So was renting a studio and pressing up records.

TH: Did that transform you as an artist? Playing the "weird" instrument, being the "weird" composer doing the "weird" sounds? Did that diminish your ambition?

SC: Well, artists need a frame, a context to start with. The commercials I worked on were wonderful little worlds you could enter. I did a lot of very short things. 3 seconds. One project I worked on was only a third of a second long, yet a whole composition. I loved the idea of these microcosms. Also, I had complete freedom, because nobody had a clue how to do what I did. It was an anonymous art form, but also very freeing and liberating. Of course there were problems as well. For instance, I could not join the union, because synthesizers back then were seen as a thread to replace musicians. Copyright was another one. I could not protect it -- my compositions were simply too short and there was no score. How do you score sounds like that? Today, I look at these years as a transitional period, which thankfully was very lucrative as well. All I wanted to do was to record my own album.

Suzanne Ciani’s sound design for a washing machine from GE

TH: Over the last couple of years, multi-channel sound systems have become more and more popular, the Hexadome is one example of how to present music in a more spacial way. You must finally feel at home.

SC: It makes me very happy, because there is still a lot of unfinished business. When I moved to New York in the 70s, I was actually able to find an agent who booked a show for me at the Lincoln Center. However, I did not play there in the end, simply because the people in charge were not willing to set up a quadrophonic system. They just didn’t understand what I was talking about. Later on, I even founded a non-profit organization called "The Electronic Center For New Music", signing up key people from the audio world for the board to promote the idea of quadrophonic. At the time, the Lincoln Center was renovating the Avery Fisher Hall, which is now called the David Geffen Hall, and they were running into acoustic problems. I went back and told them to look ahead and accommodate this new kind of music -- they still wouldn’t listen to me. "You’re not Leonard Bernstein", they told me. By the time I met the ISM crew, I actually did not want to renovate the world anymore. But I strongly feel that this is what the project is all about. There is a clear need for a space for this type of spacial music, more than ever, actually. All those concepts we were working on in the 70s are making a comeback. Quad recordings, quad performances, performing on analoge electronic instruments. All of our unfinished business from back then is back on the agenda. So obviously, I’m very happy. I feel like Sleeping Beauty. I went to sleep for 40 years and when I woke up, the world suddenly was all I ever dreamed of.

Suzanne Ciani

TH: It was Andy Votel from the Finders Keepers label who quite literally woke you up, wanting to release some of your old material.

SC: I was quite shocked when I realized that people were actually interested, it wasn’t something I was prepared for. I did not know Andy at the time and had never heard of his label either. I thought to myself, sure, let an obscure label in Manchester, UK have the tracks I never wanted to release anyway, Nobody will even notice that this record exists. Turns out, I was very wrong. I underestimated the digital age we live in. The fans of my piano records found the Finders Keepers record on Amazon and did not know what to make of it. There was rage. When Andy wanted to set up a show in Los Angeles and have me performing, I told him just not to put my name on the flyer. Today, I’m fine with it.

TH: Experiencing music in a space like Hexadome is something unique. Yet, is there more to it than just listening? An educational aspect? Modular synths are more popular than ever, heritage matters.

SC: First of all, to me electronic music today is like a huge umbrella with many valid things going on underneath. That’s great. I’m especially interested in the live performance of analoge modular instruments and there is a very healthy subculture for that. I go and see concerts and I play my own shows all over the world. It’s cool that many Eurorack modules are actually so affordable, so people get the chance to give it a try and are able to experiment. Looking at the scene, though, I still see a design gap, which Buchla back in the day tried to overcome. We need to get a conversation going and study his designs in order to come up with better instruments. Right now, they are not even close. Today, modules are regarded as little pieces you collect and turn them into systems. Why does nobody think of them as integrated instruments, make them portable and aimed at performing the music? That’s what I miss. The interface is another problem, there is just not enough visual feedback, which makes them hard to use, especially live. With the Buchla, I’m happy that if you make gesture, it results in a perceivable change in the music. That’s the whole beauty of analog -- there is no memory. Anything that happens has to do with doing something. Today, you have kids just pressing play on their laptops. It’s boring for everybody, although valid in the sense of presenting a composition. So all shortcomings aside, I’m thankful that the modular scene exists, which is much more about being in the moment and feeling alive.

Interview conducted by Thaddeus Hermann (Das Filter) on behalf of the Institute for Sound and Music, March 2019 in Berlin, Germany.

Suzanne Ciani - https://www.sevwave.com/

Das Filter - http://dasfilter.com/

ISM Hexadome North America Premiere

The Institute for Sound & Music is proud to announce the US premiere of the acclaimed ISM Hexadome installation in partnership with Gray Area Festival at the historic Pier 70 location in San Francisco from July 25th through August 4th.

Berlin’s ISM Hexadome Is What Immersive Audiovisual Art Has Been Missing

On one dreary and rain-soaked afternoon in March, Boston native Nick Meehan sat on two small granite steps leading into the large, ornate atrium of Berlin’s Martin Gropius Bau. He looked out into the barren, empty space that would eventually host the ISM Hexadome exhibition.