27.04.2018

Berlin’s ISM Hexadome Is What Immersive Audiovisual Art Has Been Missing

On one dreary and rain-soaked afternoon in March, Boston native Nick Meehan sat on two small granite steps leading into the large, ornate atrium of Berlin’s Martin Gropius Bau.

He looked out into the barren, empty space that would eventually host the ISM Hexadome exhibition. “That’s where it was bombed during World War II,” he said as he pointed out the break in the ceiling’s crown molding. The obvious gap in design from one panel to the next reflected the differences between the artists that would eventually exhibit there.

Over a month later, the ISM Hexadome concluded while hosting a crowd of artists, organizers, fans and supporters. It was impossible to tell which was which. Above it, on the balcony overlooking the structure of metal, screens and sound, Meehan could be seen gazing out at the same space, this time, filled with life, exchange and energy.

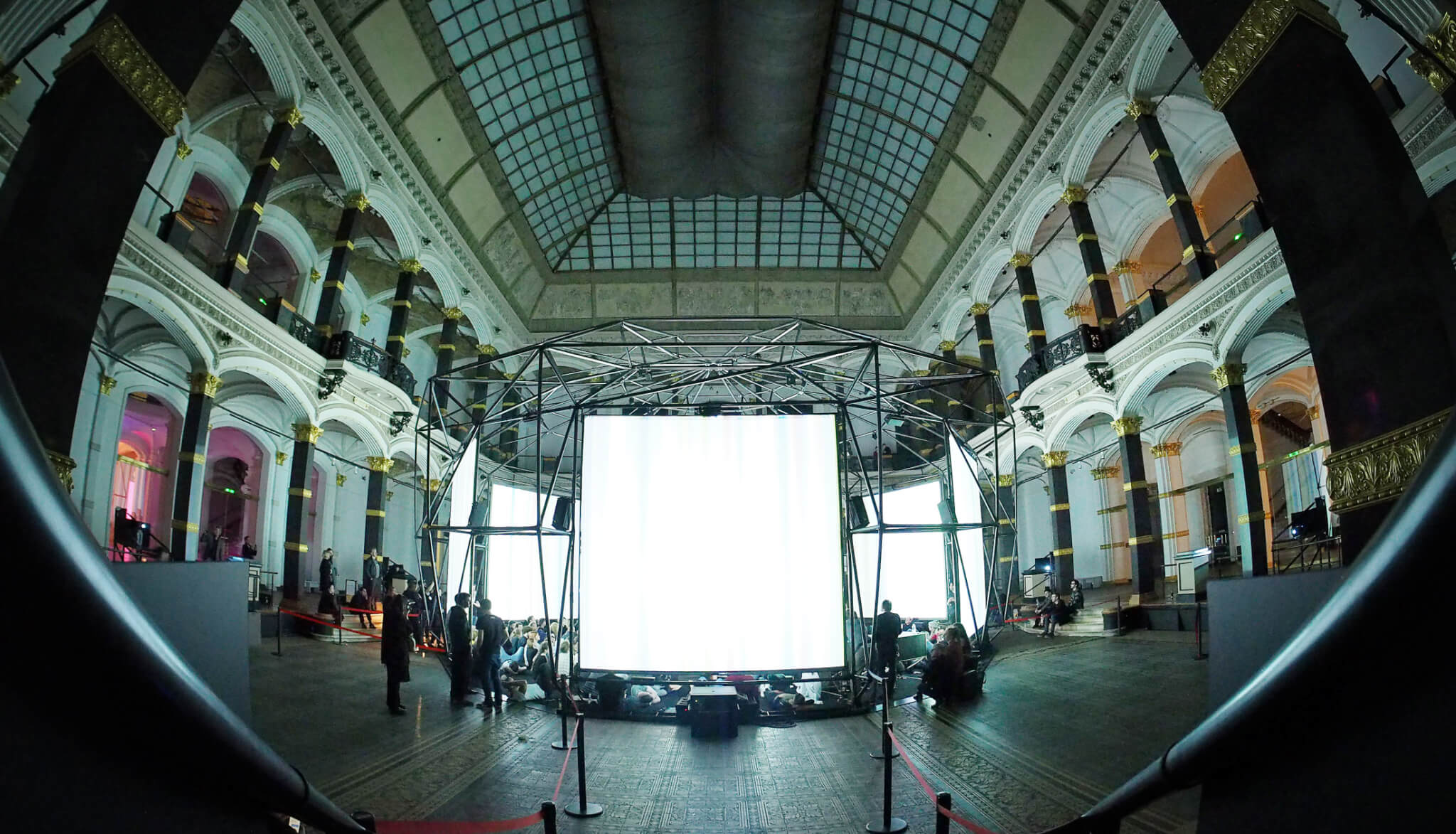

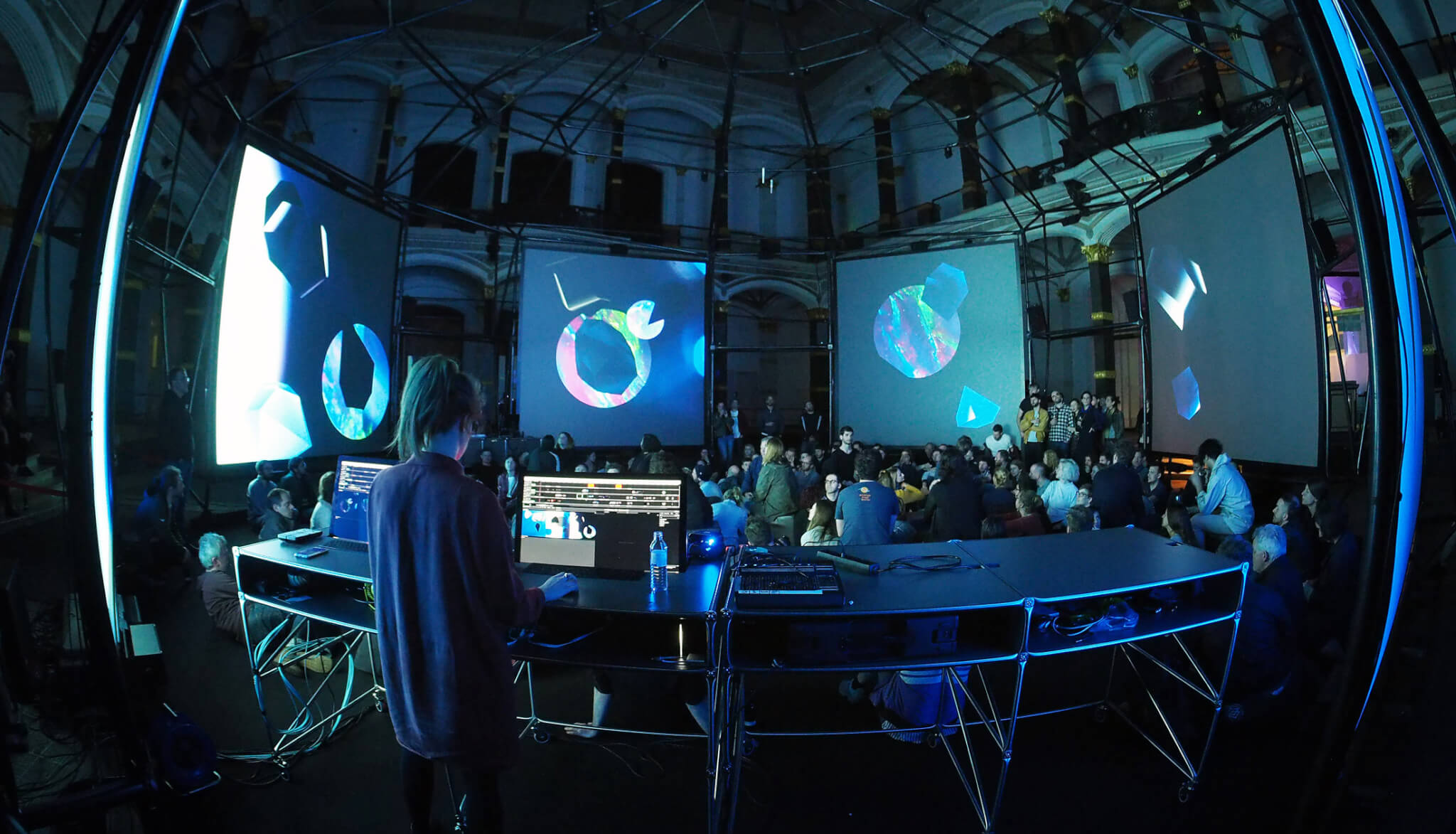

The ISM Hexadome exhibited at Berlin’s Gropius Bau from March 29 until April 22. Designed by the Berlin-based Pfadfinderei collective, the hexagonal structure featured six immense projection screens and a 52-channel surround sound system, developed by the ZKM Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe.

Meehan is the co-founder and artistic director of the new Institute for Sound and Music (ISM) based in Berlin. The not-for-profit organization is trying to establish a permanent space to nurture the development of sound and electronic music, which they feel is “under-appreciated as an art form.” The blurring of margins between artist, spectator and the art became a prominent theme and the integration between the art and the community eventually became the focal point of the exhibition. It was common during performances to see artists exchanging experiences, advice and enthusiasm for not only their work, but also that of their peers.”

The ISM Hexadome was the first of three planned exhibitions. The second and third will focus on sound and electronic music, respectively. With a focus on immersive sound and art, Meehan described the exhibition as “a public campaign to generate support for this concept and ultimately make a case to make a home for it here in Berlin.” For the director of Berliner Festspiele, Thomas Oberender, the idea of immersion overlapped quite thoroughly with his own curatorial perspective. Oberender referred to the exhibition as an “instrument.” An infrastructure of projections, screens and sound systems, he saw it simultaneously as a tool and a format.

“This idea of immersion is something that is very specific,” Oberender said. “I can focus on something like this and use it like a tool to give the people a better understanding of how art and society work in our time.” Oberender proved the defining gatekeeper between the ISM Hexadome and one of Berlin’s most noteworthy museums.

Built in 1881 by its namesake architect, the renaissance-styled Gropius Bau has been a German historical monument since 1966. After being heavily damaged during World War II, it was restored in the 1970s. At Niederkirchnerstrasse 7, it sits adjacent to the Topography of Terror museum and looks north to the ghosts of Tresor and E-Werk, some of Berlin’s most important and storied nightclubs.

For the Pfadfinderei collective, it’s a coincidence that’s impossible to ignore. As a Berliner, Pfadfinderei co-founder Jan Honza Taffelt spent many nights dancing and VJing in those nightclubs radiating out from Potsdamer Platz. “We thought, ‘How can we combine those clubs’ roots with the new space—that’s a very old and interesting space—but that’s mainly used for art?’” Taffelt said. Pfadfinderei’s pragmatic minimalism is rooted in their history of playing in temporary nightclubs. They developed their style projecting on any walls they could find with the equipment they could borrow, modify or build themselves. “We wanted to build a structure that wasn’t over-designed,” Taffelt said, “that also features these Berlin roots in temporary space.”

As Taffelt and fellow Berliner René Löwe performed at the ISM Hexadome’s final showing, it was fascinating to imagine the pair twenty years earlier, in a much different Berlin, but with the same passionate interest in their work. They certainly would not have been performing in a 137-year-old museum.

Visitors often laid scattered around the room’s soft, black carpet in the darkness during the exhibitions. The spider-like metallic structure could host about 150 people and was often full for performances. The presence of the speakers went almost unnoticed, even though the room was surrounded with more than 50. The six screens consumed vastly differently levels of attention. As Brian Eno’s Empty Formalism debuted on opening weekend, most onlookers found themselves in a meditative state. But during Holly Herndonand Mat Dryhurst’s performance, Spawn Training Ceremony I, the audience was obligated to engage with the screens for instruction.

Some pieces were created exclusively for the ISM Hexadome. Others, like Dutch audiovisual artist Tarik Barri’s, built upon years of work. “Basically, it’s the ideal environment for this project that I started in 2008,” Barri said of his City Rats composition, which featured Thom Yorke. It doesn’t take six screens or 52 speakers to experience his virtual world. But according to Barri, its model expression would have the audience looking through as large of a lens as possible.

As he performed, guests spilled out of the structure. Thom Yorke traded his falsetto for spoken words. A sense of resigned melancholia floated and sank through his voice. Yorke’s face would circle and slide through the structure, at times creating a cylindrical effect. “I woke up, with a feeling that I just could not take,” Yorke whispered and then sang as Barri had his voice ricochet across the space.

Tarik Barri

The audio spatialization was as impactful as it was suggested to be. Ludger Brümmer—the head of the ZKM Center for Music and Acoustics and the chief of the ZKM Klangdom development—has been working on it since 2003. After joining the ZKM as a guest lecturer in 1993, he was eventually recruited to head up a new project that focused on spatialized sound.

After exploring several kinds of technology, Brümmer and his team at the ZKM settled on Reverb Vector Base Amplitude Panning (RVBAP) for the Klangdom. It’s a system that operates through the mapping of coordinates on a 3D grid. Brümmer said the RVBAP system was the best solution for the ISM because it enabled a more practical speaker placement. During the exhibition, speakers were placed and hung strategically in order to ensure the availability of entrances and exits. It also helped the Gropius Bau remain a presence throughout.

There will be a chance to see the installations again, but not in Berlin. While the installations may end up in a permanent ISM museum one day, for now they’ll head on tour with the ISM Hexadome. The exhibition will visit Europe and North America and commission two new pieces at each stop.

But Berlin’s geography was only the first level of the ISM’s cultural cross-pollination. It was echoed in the exhibition’s content. According to Barri, it’s something to reflect on. “The club and the museum, they are not just their own separate bubbles,” he said. “They have influences that emanate outwards to society.” From 2011 until 2016, Meehan ran Berlin’s FEED Soundspace series with a similar perspective. At a small, self-run venue in Neukölln and then at the KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Mitte, he established a unique artistic program with an attention to sound.

Meehan noticed there was a “connection starting to develop between the artists that were really looking for a place like this in absence of a platform.” During his time running FEED, he connected with artists like Tarik Barri, Frank Bretschneider and Marcel Weber (a.k.a. MFO).

Connections like those help make up the ISM’s community and team of 24 volunteers. With the help of colleagues Brendan Power, Ben Fawkes and Marie-Kristin Meier—and 141,000 euros of financial assistance from the Kulturstiftung Des Bundes—the ISM Hexadome began to take shape.

San Francisco native Lara Sarkissian is one artist who has benefited from the realization of the ISM Hexadome community. She hopes it’s a relationship that will continue. It’s something that all of the ISM community seems to believe in. The ISM’s goals don’t revolve around the ISM Hexadome alone. “It’s also unique because it’s supposed to be a platform,” Taffelt said. “It’s not just one project.”

Sarkissian was selected by the Norient Network for Local and Global Sounds and Media Culture as one of the curated sound designers in the exhibition, the other being Peruvian artist CAO. Alongside New Zealand native and Berlin-based visual artist, Jemma Woolmore, she crafted a piece rooted in a sort of ritualistic geometry. It also served as Sarkissian’s introduction to the European audiovisual community.

Using samples of Armenian rituals, Sarkissian brought a society that’s largely ignored in the West into electronic music and into a space often reserved for a much different form of art. This kind of action and engagement lent the most value to the ISM Hexadome. While innovative, the technological aspects of the project often appeared less important than the social exchange happening before, during and after the performances.

For Sarkissian, the installation itself became a form of preservation. With Armenian vocal chants and traditional drums, she shed light on part of her family history and a type of non-western music that she feels doesn’t get enough attention.

In Thresholds, together with Woolmore, she helped illustrate the ideas of constant change present in not only Armenian history, but also art and society’s ongoing relationship with it.

The idea of discourse permeated into conversation with many of the artists involved. “It’s important to have a safe space if you want to build a community,” Woolmore said. “You want to have a space where you can get feedback and critique of your work.” But right now, that space doesn’t exist, at least not in Berlin. The ISM is trying to change that, in part by changing the context typically associated with audiovisual art.

Oberender described the ISM Hexadome as an instrument the day it opened, but as exhibition continued, the relevance of his suggestion became more apparent. The Hexadome had indeed been changing the way both the artists and the audience were engaging with the art.

As Brian Eno described at the press conference surrounding his Empty Formalism exhibition, his piece had changed since arriving at the Gropius Bau. Upon experiencing the 11-second reverb quality of the main atrium, he rewrote his composition six times. Belgian producer Peter Van Hoesen did almost the same thing. “I basically discarded most of what I did in Berlin and started from scratch,” he said. “I think 70 percent of the sounds were actually created during the last residency [at ZKM Karlsruhe].” Composing for the ISM Hexadome required change in thinking.

Instead of mixing multiple channels down to two—like in a stereo mix—working with mono files was the most convenient. “You don’t mix at all, because the mixing is done in the space,” said Brümmer. The idea of a perfect stereo mix in the ISM Hexadome quickly became obsolete. “It’s a whole other beast from stereo,” Sarkissian said. “You’re literally controlling from what direction a certain sound should come from, and it’s amazing.”

It was an experience closer to every day reality than what’s typically associated with hi-fi stereo sound. Immersive sound is the environment most people live in. “It’s the most natural thing in the world,” Van Hoesen said. “We hear in surround sound.” In that way, the ISM Hexadome aligned with Oberender and Berliner Festspiele’s interest in how people interact with art in contemporary society. When sitting in ISM Hexadome, the movement of sound was actually more accurate and less noticeable than one might have initially imagined. There remained the feeling that sounds were moving, but it rarely felt unnatural enough to try to determine how or why.

It proposed more questions about the future of sound than it answered. “What does electronic music mean 20 years from now?” Meehan asked. “One of the wonderful things about this category of music and sound is that the tools that existed and the landscape of the technology have completely changed.” The ISM is challenging the ephemerality of audiovisual performance. By blurring the boundaries between influences, it’s trying to also change the limits and lifespan of sound and visual design.

“I work almost exclusively in the domain of real-time stuff, so every performance is unique,” Barri said. “It’s really nice to be living in the now, but it’s also really cool to have memory.” That sense of preservation was just one motivation on a long list for the artists involved.

For Van Hoesen, the excitement extends from his awareness that projects like the ISM Hexadome are anything but common. “I know how difficult these things are to organize, so for me I hugely appreciate the way they are doing that,” he said. “Having the opportunity to work [at ZKM] for several weeks, in the best possible scenario. The good support makes it a special project.” The ISM Hexadome ascertained its rarity not only conceptually, but in its costly attention to detail.

It remains to be seen whether the ISM will actually realize their long-term goal of establishing a museum for sound. In Meehan’s eyes, it was still worth it. “Getting to this point has been incredible because of the ISM team in general,” he said. “There is just great admiration and gratitude for what they’re doing.” And as Meehan sat in the middle of the ISM Hexadome and watched the installation reel for almost three straight hours, it was hard not to believe him.

If the ISM Hexadome proved anything about the themes it explored, like social integration through immersive art, it’s that there is a community yearning for a platform—and that there are artists willing to build it.

Publication: Electronic Beats

Original article available here

Hearing is Believing - Audio Media International

Berlin is often seen as a city that is supportive of innovation and creativity. With Germany’s strong role in technical research and development, it’s not surprising that those interested in sonic experimentation are drawn to the country’s capital.

Enter the Hexadome - Louder magazine

What do you get when you place Brian Eno, Thom Yorke and other artists inside a large metal structure fitted with six giant screens and over 50 speakers? An audiovisual revelation.